Andronikos I Komnenos

| Andronikos I Komnenos | |

|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |

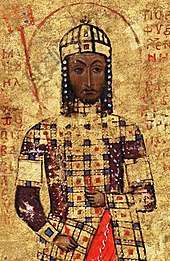

Miniature portrait of Andronikos I (from a 15th-century codex containing a copy of the Extracts of History by Joannes Zonaras) | |

| Byzantine emperor | |

| Reign | September 1183 – 12 September 1185 |

| Predecessor | Alexios II Komnenos |

| Successor | Isaac II Angelos |

| Co-emperor | John Komnenos |

| Born | c. 1118–1120 |

| Died | 12 September 1185 (aged 64–67) Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Spouse | Unknown first wife Agnes of France |

| Issue | Manuel Komnenos John Komnenos Maria Komnene Alexios Komnenos Irene Komnene |

| Dynasty | Komnenos |

| Father | Isaac Komnenos |

| Mother | Irene |

Andronikos I Komnenos (Greek: Ἀνδρόνικος Κομνηνός; c. 1118/1120 – 12 September 1185), Latinized as Andronicus I Comnenus, was Byzantine emperor from 1183 to 1185. A nephew of John II Komnenos (r. 1118–1143), Andronikos rose to fame in the reign of his cousin Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180), during which his life was marked by political failures, adventures, scandalous romances, and rivalry with the emperor.

After Manuel's death in 1180, the elderly Andronikos rose to prominence as the accession of the young Alexios II Komnenos led to power struggles in Constantinople. In 1182, Andronikos seized power in the capital, ostensibly as a guardian of the young emperor. Andronikos swiftly and ruthlessly eliminated his political rivals, including Alexios II's mother and regent, Maria of Antioch. In September 1183, Andronikos was crowned as co-emperor and had Alexios murdered, assuming power in his own name. Andronikos staunchly opposed the powerful Byzantine aristocracy and enacted brutal measures to curb their influence. Although he faced several revolts and the empire became increasingly unstable, his reforms had a favorable effect on the common citizenry. The capture of Thessaloniki by William II of Sicily in 1185 turned the people of Constantinople against Andronikos, who was captured and brutally murdered.

Andronikos was the last Byzantine emperor of the Komnenos dynasty (1081–1185). He was vilified as a tyrant by later Byzantine writers, who denigrated him with the nickname "Misophaes" (Greek: μισοφαής, lit. 'hater of sunlight') in reference to the great number of enemies he had blinded. The anti-aristocratic policies pursued by Andronikos destroyed the Komnenian system implemented by his predecessors. His reforms and policies were reversed by the succeeding Angelos dynasty (1185–1204), which contributed to the collapse of imperial central authority. When the Byzantine Empire was temporarily overthrown in the Fourth Crusade (1204), Andronikos's descendants established the Empire of Trebizond, where the Komnenoi continued to rule until 1461.

Early life and character

[edit]Andronikos Komnenos was born in c. 1118–1120,[1] the son of the sebastokrator Isaac Komnenos[2] and his wife Irene.[1] Andronikos had three siblings: the older brother John and two older sisters, one of which was named Anna.[3] Andronikos was the nephew of the reigning emperor, John II Komnenos (r. 1118–1143), and grew up together with his cousin (and John's successor) Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180).[1]

In 1130, Andronikos's father was involved in a conspiracy against John II while the emperor was away from Constantinople on campaign against the Sultanate of Rum. The conspiracy was uncovered but Isaac and his sons fled the capital and found refuge at the court of the Danishmendid emir Gümüshtigin Ghazi at Melitene.[4] The family spent six years on the run, traveling to Trebizond, Armenian Cilicia, and eventually the Sultanate of Rum, before Isaac reconciled with John II and the emperor forgave him.[5]

According to the historian Anthony Kaldellis, Andronikos was "one of the most colorful and versatile personalities of the age".[6] He was tall, handsome, and brave, but a poor strategist,[2] and was known for his good looks, intellect, charm, and elegance.[7]

Reign of Manuel I (1143–1180)

[edit]Imperial career

[edit]

Manuel I Komnenos began his reign as emperor on good terms with Andronikos. Andronikos showed no signs of treachery towards his cousin and Manuel was fond of his company since the two were of similar age and had grown up together.[8] Andronikos took offence when officials spoke badly of Manuel's governance and was lent Manuel's favorite horse while they were on military campaigns.[8] Similar in personality, the friendship between Manuel and Andronikos only gradually transitioned into rivalry.[9]

Manuel never succeeded in integrating Andronikos into the imperial family power network. Although talented and impressive as a person, Andronikos typically handled tasks entrusted to him carelessly.[1] Relations between Manuel and Andronikos deteriorated in 1148, when Manuel appointed his favorite nephew John Doukas Komnenos as protovestiarios and protosebastos.[8] These appointments were the last in a long line of extraordinary favors given to John[10] and greatly wounded Andronikos, who from then on became involved in various intrigues against the emperor.[8]

In 1151–1152, Manuel sent Andronikos with an army against Thoros II of Armenian Cilicia, who had conquered large parts of Byzantine-held Cilicia.[11] The campaign was a dismal failure, as Thoros defeated Andronikos and occupied even more of Cilicia.[11] Andronikos was nevertheless made governor of the portions that remained in imperial control.[8]

In the winter of 1152–1153, the imperial court was at Pelagonia in Macedonia,[12] perhaps for recreational hunting.[13] During the stay there, Andronikos slept in the same tent as Eudokia Komnene, Manuel's niece[14] and sister of John Komnenos Doukas,[12] committing incest.[15] When Eudokia's family attempted to catch the two in the act[15] and assassinate Andronikos,[13] he escaped by cutting a hole in the side of the tent with his sword.[13][14] Manuel criticized the affair but Andronikos answered him that "subjects should always follow their master's example", alluding to well-founded rumors of the emperor himself having an incestuous relationship with Eudokia's sister Theodora.[16]

Andronikos actively conspired against Manuel in the early 1150s, together with Baldwin III of Jerusalem and Mesud I of Rum.[8] He was then removed from his command in Cilicia and transferred to oversee the governance of Branitzova and Naissus in the west. Not long thereafter, Andronikos promised to turn over these towns to Géza II of Hungary in return for aid in seizing the imperial throne.[8] In 1155, Andronikos was imprisoned by Manuel in the imperial palace.[2] According to Niketas Choniates, the imprisonment was a direct result of his plot to usurp the throne with Hungarian aid, and his affair with Eudokia.[8] John Kinnamos, however, claims that Manuel knew of the intrigues and did not punish Andronikos until he uttered death threats to John Komnenos Doukas.[8]

Escapes from prison

[edit]

Andronikos escaped from prison in 1159, while Manuel was away on campaign in Cilicia and Syria.[9] Having discovered an ancient underground passage beneath his cell, he dug his way down using only his hands and managed to conceal the opening so that the guards were unable to find any damage to the cell.[17] The escape was reported to Manuel's wife, Empress Bertha-Irene, and a great search was ordered in Constantinople. In Andronikos's stead, his wife was briefly imprisoned in the same cell. According to Niketas Choniates, Andronikos soon emerged up into the cell again, embraced and had sex with his wife, conceiving his second son John. Andronikos then escaped the capital but was caught in Melangeia in Thrace by a soldier named Nikaias and imprisoned again with stronger chains and more guards.[17]

Andronikos escaped prison for a second time in 1164.[18] He had pretended to be ill and was provided with a boy to see to his physical needs. Andronikos convinced the boy to make wax impressions of the keys to his cell and to bring these impressions to Andronikos's elder son, Manuel. Manuel forged copies of the keys, which the boy used to let Andronikos out.[19] Andronikos spent three days hiding in tall grass near the palace, before trying to flee in a fishing boat alongside a fisherman named Chysochoöpolos. The two were caught by guards, but Andronikos convinced them that he was an escaped slave and was let go out of compassion. Andronikos then made his way to his home, said goodbye to his family, and fled the capital,[20] traveling beyond the Carpathian Mountains.[21]

Andronikos first spent some time in Halych, where he was briefly captured by Vlachs from Moldavia[22] who intended to bring him back to Manuel.[20] During his captivity, Andronikos pretended to suffer from infectious diarrhea, requiring frequent stops to dismount and defecate alone and at a distance. One night, he made a dummy out of his cloak, hat, and staff, in the position of a man defecating. While the Vlachs watched the dummy, Andronikos managed to escape.[23] He then made his way to Galicia, where he was well received by Prince Yaroslav Osmomysl.[24]

During his time at Yaroslav's court, Andronikos tried to recruit the Cumans to aid him in an invasion of the Byzantine Empire.[25] Despite these efforts, Manuel sought to reconcile with him and managed to form an anti-Hungarian alliance with Yaroslav.[25] When the Byzantines and Galicians joined forces in a combined invasion of Hungary in the 1160s, Andronikos led a force of Galicians and assisted Manuel during a siege of Semlin.[26] The campaign was a success and Andronikos returned with Manuel to Constantinople.[26] In 1166,[2] Andronikos was removed from court for refusing to take an oath of allegiance to then designated heir, Béla III of Hungary,[26] but was entrusted once again to govern Cilicia.[2]

Exile

[edit]

In 1167,[27] Andronikos deserted his post in Cilicia and traveled to Antioch, where he seduced Philippa of Antioch.[2] Philippa was the sister of both Manuel's second wife Maria[2] and Bohemond III, the reigning prince of Antioch.[16] The affair caused a scandal[28] and threatened to jeopardize Manuel's foreign policy.[2] Bohemond formally complained to the emperor that Andronikos was neglecting his duties in Cilicia and instead dallying with Philippa.[27] Manuel was outraged and immediately recalled Andronikos,[16] replacing him as governor in Cilicia with Constantine Kalamanos.[27] Kalamanos was also dispatched to attempt to wed Philippa. Upon meeting Kalamanos, the princess refused to address him by name, berated him for being short, and derided Manuel as "stupid and simple-minded" for believing she would forsake Andronikos for a man from such an obscure family line.[29] Andronikos refused to return home and instead fled with Philippa to Jerusalem,[27] where King Amalric gave him Beirut as a fief to govern.[27][28]

Andronikos left Philippa in 1168[27] and instead seduced the dowager queen Theodora Komnene, widow of Amalric's brother Baldwin III and daughter of Andronikos's cousin Isaac.[2] Theodora was 21 years old at the time.[7][16] The historian John Julius Norwich has described Theodora as the love of Andronikos's life,[7][16] though their close relation made them unable to marry.[16] Manuel was furious over this affair as well and again ordered Andronikos to return home. Fearing that Amalric would back Manuel, Andronikos feigned acceptance. He traveled to Acre without Theodora, though she suddenly arrived after him and the two eloped together to the court of Nur al-Din Zengi in Damascus.[27] The arrival of a Byzantine prince and a dowager-queen of Jerusalem in Damascus became a sensation in the Muslim world and they were welcomed with much enthusiasm.[30]

Andronikos and Theodora traveled from court to court for several years,[2] making their way through Anatolia and the Caucasus.[26] They were eventually received by George III of Georgia and Andronikos was granted estates in Kakhetia. In 1173 or 1174, Andronikos accompanied George on a military expedition to Shirvan up to the Caspian shores, where the Georgians recaptured the fortress of Shabaran from invaders from Darband for his cousin, the Shirvanshah Akhsitan I.[31]

Andronikos and Theodora eventually settled in Koloneia in northeastern Anatolia, just beyond the frontier of the Byzantine Empire.[16] Their peaceful life there came to an end when imperial officials captured Theodora[2] and their two children and brought them to Constantinople.[16] After over a decade in exile,[1] Andronikos returned to Constantinople in 1180 and theatrically pleaded for forgiveness from Manuel with a chain around his neck,[2] begging that Theodora and the children be returned.[16] The two reconciled, and Andronikos was sent to govern Paphlagonia,[2] where he lived with Theodora in a castle on the Black Sea coast.[16] The arrangement was understood as internal exile[32] and peaceful retirement.[16] Theodora's ultimate fate is not known, though she likely died before Andronikos's return to imperial politics in 1182.[30]

Reign of Alexios II (1180–1183)

[edit]Power struggle

[edit]

Manuel died on 24 September 1180[33] and the throne was inherited by his eleven-year-old son, Alexios II Komnenos.[6] A regency was set up for the young emperor, led by Manuel's widow, Maria of Antioch.[34] Manuel had made his officials and nobles swear to obey Maria as regent, on the condition that she became a nun (which she did) and guarded the honor of the empire and their son.[35] Maria was supported by Patriarch Theodosios Borradiotes and the prōtosebastos Alexios Komnenos, a nephew of Manuel.[34] Despite this, she was in a dangerous position. She was of Latin (i.e. Catholic/Western European) origin and regent for a minor with ambitious relatives.[35] Manuel had throughout his reign sought to integrate the empire into the world of the Latin states in the West and Levant through diplomacy. His efforts were largely unsuccessful, as Latin polities began to regard themselves as having a say in imperial politics and anti-Latin sentiment grew among the populace of the empire.[36]

Maria of Antioch was young and beautiful, leading to power struggles between officials who sought her favor.[35] Little political attention was given to Alexios II, who as a child was devoted entirely to pursuits such as chariot races and hunting.[37] The perceived pro-Latin stance of the regency and rumors that Maria and Alexios the prōtosebastos were lovers, as well as suspicions that the prōtosebastos planned to seize the throne for himself, led to the formation of a court faction opposed to the regency.[34][35] Some of Maria's supporters also began to abandon her as the favors they sought were increasingly given to the prōtosebastos.[37] The opposition was led by Manuel's daughter, Maria Komnene, her husband Renier of Montferrat,[6][34] and Manuel's illegitimate son Alexios.[37]

In early 1181, a plot to assassinate the prōtosebastos was uncovered and many were arrested.[34] Maria Komnene and Renier sought asylum in the Hagia Sophia[6][37] and were supported by Patriarch Theodosios and the clergy.[37] The two conspirators turned the church into a stronghold and issued demands that the prōtosebastos be removed from office and that those arrested should be released.[37] The citizenry of Constantinople were split between the two factions. Clashes erupted throughout the capital,[6] lasting for two months.[34] Maria Komnene, supported by the clergy, portrayed her revolt against the regency as a holy war.[37] With the government focused on the power struggle, the empire swiftly lost territory to foreign enemies. Béla III of Hungary conquered Dalmatia and Sirmium, and Kilij Arslan II of Rum conquered Sozopolis and besieged Attaleia.[6]

Peace was brokered in the capital by the megas doux Andronikos Kontostephanos[6] and the patriarch[37] but the conflict was not resolved.[34] In 1182,[34] Maria Komnene and other nobles sent for Andronikos in Paphlagonia, inviting him to the capital to assume the protection of Alexios II.[38] Andronikos was by this time in his early sixties and regarded by some as an elder statesman.[2] Because of his exile away from the affairs in the capital, he was seen as an impartial outsider who could champion the young emperor's best interests.[39] Maria Komnene could also assume that he would be supportive of her since Andronikos's sons Manuel and John had been involved in her revolt.[38] In the spring of 1182, Andronikos assembled an army and marched on Constantinople.[34] He portrayed himself as a champion of Alexios II,[2] accused Maria of Antioch and the prōtosebastos of conspiracy, and falsely claimed that Manuel had appointed him as one of Alexios II's regents.[38] The general Andronikos Angelos was sent to intercept Andronikos but was defeated, fled back to Constantinople, and quickly defected to Andronikos out of fear of his failure being punished.[2] Once Andronikos reached the Bosporus, public opinion in Constantinople was firmly on his side.[40] The prōtosebastos organized a fleet to stop Andronikos, led by Kontostephanos, though Kontostephanos likewise defected to the rebel's side.[2]

Regent in Constantinople

[edit]

With no military forces left to oppose Andronikos, the prōtosebastos was taken captive and taken across the Bosporus to Andronikos's camp,[40] where he was blinded.[2] Andronikos then ferried his troops to the city and took control virtually without opposition.[40] He almost immediately made his way to the Pantokrator Monastery, apparently to pay his respects to the tomb of Manuel.[41]

Soon after Andronikos gained control of Constantinople in April 1182, the Massacre of the Latins erupted in the city.[42] Andronikos made no effort to stop the pogroms, instead referring to them as a "defeat of the tyranny of the Latins" and a "restoration of Roman affairs". There is no evidence that Andronikos was particularly anti-Latin on a personal level but the massacre was politically useful since anti-Latin sentiment had helped bring him to power and because many Latins in the city had supported Maria of Antioch's regency.[2] The bulk of Constantinople's Latin population were either killed or forced to flee[43] and the Latin quarters were plundered and set on fire.[2] According to Eustathius of Thessalonica, approximately 60,000 people were killed[43][44] though this number is likely exaggerated.[44] A papal delegate visiting Constantinople was decapitated and his head was tied to the tail of a dog.[2]

In May, Patriarch Theodosios formally handed Constantinople over to Andronikos. The patriarch and Andronikos ensured that Alexios II was formally crowned as emperor on 16 May 1182. Andronikos carried the young emperor into Hagia Sophia on his shoulders and acted as a devoted supporter.[44] Andronikos soon dealt with his political rivals as well as all major schemers during Maria of Antioch's regency, including those who had supported him. The blinded prōtosebastos was exiled to a monastery. Both Maria Komnene and Renier of Montferrat were poisoned within a few months.[41] Andronikos Kontostephanos was suspected of conspiracy and blinded alongside his four sons in the summer of 1183.[41] Maria of Antioch remained an obstacle since she was legally appointed as regent. Andronikos had Patriarch Theodosios agree on expelling her from the palace and then had her prosecuted for treason on the basis that she had asked her brother-in-law, Béla III of Hungary, for help.[44] Found guilty, Maria was imprisoned[44] and Andronikos had Alexios II sign a document condemning her to death.[45] The empress was strangled to death and subjected to damnatio memoriae, with her portraits in public places being replaced with imagery of Andronikos.[41]

In the place of Manuel's officials, Andronikos raised up his own loyalists, such as Michael Haploucheir and Stephen Hagiochristophorites.[41] The execution of Maria of Antioch left the young Alexios II without protection.[45] Andronikos had some of the clergy formally absolve him of his oaths to Manuel and Alexios II[46] and was crowned as co-emperor in September 1183.[47] Soon thereafter, Alexios II was strangled and his body was thrown in the sea, encased in lead.[45] Just over a year after taking power as the young emperor's guardian, Andronikos had thus had him suppressed and killed[1] and now ruled in his own name.[47]

Reign (1183–1185)

[edit]

Andronikos's assumption of sole power rapidly plunged the empire into further instability. The elimination of Alexios II made Andronikos dependent on a power base bound only to him through self-interest.[39] In Alexios's place, Andronikos in November 1183 named his son John as co-emperor and heir. The choice likely fell on the younger John rather than the older son, Manuel, since John was considered more loyal and his name adhered to the AIMA prophecy.[48] One of the only members of the previous immediate imperial family to survive Andronikos's rise to power was Agnes of France, Alexios II's young French wife.[49] To increase his legitimacy,[49] the elderly Andronikos controversially married the eleven-year-old empress.[50]

Andronikos concentrated his political efforts on internal affairs[1] and was determined to curtail the power of the aristocracy and stop corruption,[47] returning absolute control of the state to the hands of the emperor.[1] Under the preceding Komnenoi emperors, regional magnates had acquired vast power, managing their administrations at will and exploiting peasants and common citizens.[1] Although often brutal, Andronikos was generally successful in his anti-aristocratic measures and his policies had a favorable effect on the citizenry.[47] Because the emperor directly endangered their positions, aristocrats were uncooperative and many rose in revolt, in turn being suppressed with cruelty and terror.[1] The situation soon evolved into a reign of terror where even suspicion of disloyalty could result in disgrace and execution.[1] There were imperial spies everywhere, night arrests, and sham trials.[50] Andronikos's purges were not limited to Constantinople.[41] In the spring of 1184, the emperor marched into Anatolia to punish the cities of Nicaea and Prusa, which opposed his accession.[49] The rebels included the aristocrat Isaac Angelos and his family. During the siege, Andronikos had Isaac's mother Euphrosyne placed on top of a battering ram[51][52] to deter the defenders from trying to destroy it.[52] After Prusa was taken by storm, several of the defenders were impaled outside the city walls,[41][49] though Isaac was spared due to surrendering in return for immunity.[53]

Other than his brutal suppression of aristocrats, Andronikos attempted to put sensible policies in place to secure the well-being of the peasantry and provincial administration of the empire. The taxation system was overhauled in an attempt to root out corruption and ensure that only regular taxes were paid (and not surcharges imposed by tax farmers). He further legislated that offices for collecting revenue were to be awarded based on merit and not sold to the highest bidder.[50][54] Andronikos was receptive to accusations against aristocrats by the common people and the prosperity of the provincial population increased under his rule.[55] The emperor actively responded to complaints of inequality and corruption, and tried to shorten the gap between the provinces and the capital, seeking to solve problems that had originated in Manuel's pro-aristocratic reign.[55]

The brutality enacted against the ruling class caused the alliances built up under Manuel in the Balkans to fall apart. Béla III of Hungary invaded the empire in 1183, posing as an avenger of Maria of Antioch, but was driven away in 1184. During this conflict, Stefan Nemanja managed to secure Serbian independence from the empire.[47] The suppression of aristocrats and rivals, some of whom were Andronikos's family members, led to many Byzantine nobles fleeing the empire in search of aid.[47] Komnenian princelings are recorded as having approached figures such as the king of Hungary, the sultan of Rum, the marquis of Montferrat, the pope, the king of Jerusalem, and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa with pleas of intervention, stirring up further trouble against the empire.[39] In 1184, Andronikos's cousin Isaac Komnenos seized Cyprus and ruled there independently;[55] in retaliation, Andronikos had two of Isaac's relatives stoned and impaled.[53]

Downfall and death

[edit]

In 1185, the pinkernēs Alexios Komnenos, a great-nephew of Manuel, approached William II of Sicily with a request for aid against Andronikos. William invaded the Byzantine Empire and successfully captured both Dyrrhachium and Thessaloniki in the name of a young man pretending to be Alexios II.[39] The capture of Thessaloniki in August 1185[1] was followed by a brutal sack of the city, portrayed by the chronicler William of Tyre as if the Sicilians were "making war on God himself", and as revenge for the Massacre of the Latins.[56] With Thessaloniki captured, the Sicilians turned their eyes towards Constantinople.[53] The war, however, slowly shifted in Andronikos's favor. The Byzantines successfully split up the invaders into several smaller forces and were slowing down their advance eastwards.[1] Despite beginning to turn the tide, the atmosphere in Constantinople was tense and fearful[1] and the fall of Thessaloniki had turned the common people of the city, previously strong supporters of Andronikos, against the emperor.[47]

During this time, Andronikos sent Stephen Hagiochristophorites to arrest the earlier rebel Isaac Angelos,[57] who was a matrilineal relative of the Komnenos dynasty.[58] Isaac panicked, killed Hagiochristophorites, and sought refuge in the Hagia Sophia.[1] Finding himself at the center of popular demonstrations against Andronikos,[49] Isaac unwittingly became the champion of an uprising and was proclaimed emperor.[1] Andronikos tried to flee Constantinople in a boat but was captured and brought to Isaac.[26][49]

Isaac handed Andronikos over to the incensed people of Constantinople. Andronikos was tied to a post and brutally beaten for three days. Alongside numerous other punishments, his right hand was cut off, his teeth and hair were pulled out, one of his eyes was gouged out, and boiling water was thrown in his face.[26] Andronikos was then taken to the Hippodrome, where he was hung by his feet between two pillars. Two Latin soldiers competed over whose sword could penetrate his body more deeply and Andronikos's body was torn apart.[59] According to Niketas Choniates, Andronikos endured the brutality bravely and retained his senses throughout the ordeal.[60] He died on 12 September 1185[61] and his remains were left unburied and visible for several years afterwards.[59] At the news of Andronikos's death, his son and co-emperor John was murdered by his own troops in Thrace.[59]

Family

[edit]

Andronikos was married twice and had numerous mistresses. He had three children with his first wife, whose name is not recorded:[62]

- Manuel Komnenos (1145–after 1185), an ambassador under Manuel I and opposed to many of the policies of his father. Manuel was blinded by the new regime established by Isaac Angelos and disappears from the sources thereafter.[63] He was married to the Georgian princess Rusudan and the couple had two sons, Alexios and David Komnenos. In 1204, Alexios and David founded the Empire of Trebizond, which continued to be ruled by their descendants.[64][65] Trapezuntine efforts to gain influence and power in the wider Byzantine world were hindered both by geography and by their emperors descending from Andronikos.[66]

- John Komnenos (1159–1185), co-emperor with Andronikos.[67] Murdered by his own troops after Andronikos's death in September 1185.[59]

- Maria Komnene (born c. 1166), married to the nobleman Theodore Synadenos in 1182 and then to a nobleman named Romanos. Romanos is noted for mishandling the defence of Dyrrhachium against the Sicilians in 1185. The fates of Maria and Romanos after Andronikos's death are unknown.[68]

Andronikos had no children with his second wife, Agnes of France, nor any known illegitimate children with any of his mistresses other than his long-term partner Theodora Komnene, with whom he had two:[69]

- Alexios Komnenos (1170–c. 1199), fled to Georgia after 1185, where he married into the local nobility. Claimed descendants include the noble family of Andronikashvili.[70]

- Irene Komnene (born 1171), married to the sebastokrator Alexios Komnenos, an illegitimate son of Manuel I. Alexios was involved in a conspiracy in October 1183, whereafter he was blinded and imprisoned and Irene became a nun.[71]

Legacy

[edit]Andronikos's fall from power ended the rule of the Komnenos dynasty, which had governed the Byzantine Empire since 1081. He was vilified as a tyrant in Byzantine writings after his death.[54] The later Angeloi emperors made it official imperial policy that Andronikos had been a tyrant, echoed in all texts addressed to them or their officials. This policy included changing earlier texts; in the writings of Theodore Balsamon, for instance, all references to Andronikos as basileus (emperor) were replaced by tyrannos.[50] Andronikos eventually received the epithet "Misophaes" (Greek: μισοφαής, lit. 'hater of sunlight') in Byzantine historiography, in reference to the great number of enemies he had blinded.[72]

The earlier Komnenoi emperors had instituted the Komnenian system of administration, family rule, and financial and military obligations. This system allowed the empire to achieve prosperity and some internal stability. It also greatly increased the power and wealth of the landowning provincial aristocracy.[73] Aristocrats had become able to run their administrations at will, exploit common citizens,[1] and withhold funds from the central government to use for their own purposes.[73] At its extreme, this could allow for independent local governments, such as that of Isaac Komnenos in Cyprus and the later realm ruled by Leo Sgouros in the Peloponnese.[73] The power and abuses of the aristocracy was a very real issue, recognized by Andronikos, which ultimately contributed to the empire's catastrophic decline after his death.[54]

Through his reforms and brutal suppression, Andronikos destroyed the Komnenian system,[73] though his death ended all attempts to curb the power of the aristocracy.[47] Over the course of the subsequent Angelos dynasty, aristocratic power instead increased and the empire's central authority collapsed.[47] Though blame for Byzantine decline has in the past been levied at Andronikos's brutal rule, his brutal efforts did little damage to the empire's long-term stability since they were largely confined to the ruling class, mostly in Constantinople itself.[54] His domestic reforms were largely sensible, though imposed too hastily, and his brutal fall from power after a short reign stopped any chance of repairing the system.[54] The Angeloi emperors, Isaac II Angelos (r. 1185–1195) and Alexios III Angelos (r. 1195–1203), faced problems of manpower directly resulting from the increasingly decentralized empire.[74]

The historian Paul Magdalino suggested in 1993 that Andronikos's reign saw the setting of the precedents that allowed the Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) to transpire, including an increasingly anti-Latin foreign policy as well as the phenomenon of relatives of the imperial family traveling abroad in the hope of securing foreign intervention in imperial politics.[39]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Kislinger 2019, p. 77.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Kaldellis 2024, p. 697.

- ^ Varzos 1984a, pp. 254, 480–638.

- ^ Varzos 1984a, pp. 239, 480.

- ^ Varzos 1984a, pp. 243–244, 481.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kaldellis 2024, p. 696.

- ^ a b c Norwich 1998, The Fourth Crusade.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Magdalino 2002, p. 197.

- ^ a b Magdalino 2002, p. 198.

- ^ Magdalino 2002, p. 196.

- ^ a b Treadgold 1997, p. 642.

- ^ a b Jeffreys 2017, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Garland 2017, Imperial Women and Entertainment at the Middle Byzantine Court.

- ^ a b Kaldellis 2009, p. 92.

- ^ a b Jeffreys 2017, p. 186.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Norwich 2018, Against Andronicus.

- ^ a b Choniates 1984, p. 61.

- ^ Magdalino 2002, p. 205.

- ^ Choniates 1984, p. 73.

- ^ a b Choniates 1984, p. 74.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 131.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 132.

- ^ Choniates 1984, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Spinei 2009, pp. 132–133.

- ^ a b Spinei 2009, p. 133.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911, p. 975.

- ^ a b c d e f g Venning 2015, p. 156.

- ^ a b Hamilton 2005, p. 173.

- ^ Choniates 1984, p. 80.

- ^ a b Hamilton 2018, Women in the Crusader States: the Queens of Jerusalem 1100–1190.

- ^ Minorsky 1945, pp. 557–558.

- ^ Magdalino 2008, p. 659.

- ^ Harris 2014, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harris 2014, p. 127.

- ^ a b c d Garland 1999, p. 205.

- ^ Kaldellis 2024, p. 726.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Garland 1999, p. 206.

- ^ a b c Garland 1999, p. 207.

- ^ a b c d e Magdalino 2008, p. 660.

- ^ a b c Harris 2014, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harris 2014, p. 129.

- ^ Harris 2014, p. 130.

- ^ a b Ducellier 1986, pp. 506–508.

- ^ a b c d e Garland 1999, p. 208.

- ^ a b c Garland 1999, p. 209.

- ^ Kaldellis 2009, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gregory 2010, p. 309.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 521, 529–530.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris 2020, 12.1.

- ^ a b c d Kaldellis 2024, p. 700.

- ^ Choniates 1984, pp. 156–157.

- ^ a b Kaldellis 2009, p. 94.

- ^ a b c Treadgold 1997, p. 654.

- ^ a b c d e Harris 2020, 12.2.

- ^ a b c Kaldellis 2024, p. 701.

- ^ Siecienski 2023, p. 59.

- ^ Savvides 1994, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Gregory 2010, p. 310.

- ^ a b c d Choniates 1984, p. 193.

- ^ Kaldellis 2009, p. 96.

- ^ Choniates 1984, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Varzos 1984a, p. 637.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 511–528.

- ^ Varzos 1984a, pp. 637–638.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, p. 527.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 710.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 528–532.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 532–535.

- ^ Varzos 1984a, p. 638.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 532–537.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 481, 537–539.

- ^ Lascaratos 1999, pp. 73–78.

- ^ a b c d Birkenmeier 2002, p. 155.

- ^ Birkenmeier 2002, p. 156.

Bibliography

[edit]- Birkenmeier, John W. (2002). The development of the Komnenian army: 1081–1180. Brill. ISBN 9789004117105.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Andronicus I", Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 1 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 975–976

- Choniates, Nicetas (1984). O City of Byzantium, Annals of Niketas Choniatēs. Translated by Harry J. Magoulias. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1764-2.

- Ducellier, Alain (1986). "The death throes of Byzantium: 1080–1261". The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 950–1250. Cambridge University Press. pp. 489–524. ISBN 978-0-521-26645-1.

- Garland, Lynda (1999). Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527–1204. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14688-7.

- Garland, Lynda (2017). Byzantine Women: Varieties of Experience 800–1200. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781351953719.

- Gregory, Timothy E. (2010). A History of Byzantium (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405184717.

- Hamilton, Bernard (2005). The Leper King and His Heirs: Baldwin IV and the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521017473.

- Hamilton, Bernard (2018). Crusaders, Cathars and the Holy Places. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780429812781.

- Harris, Jonathan (2014). Byzantium and the Crusades (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781780937366.

- Harris, Jonathan (2020). Introduction to Byzantium, 602–1453. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781351368773.

- Jeffreys, Michael (2017). "Manuel Komnenos' Macedonian military camps: a glamorous alternative court?". Byzantine Macedonia: Identity, Image and History. BRILL. pp. 184–191. ISBN 978-18-76-50306-2.

- Kaldellis, Anthony (2009). "Paradox, Reversal and the Meaning of History". Niketas Choniates: A Historian and a Writer. La pomme d'or. pp. 75–100. ISBN 978-954-8446-05-1.

- Kaldellis, Anthony (2024). The New Roman Empire: A History of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197549322.

- Kislinger, Ewald (2019). "Andronikos I Komnenos". Encyclopedia of Greece and the Hellenic Tradition: Volume I: A–K. Routledge. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-1-57958-141-1.

- Lascaratos, John (1999). "'Eyes' on the Thrones: Imperial Ophthalmologic Nicknames". Survey of Ophthalmology. 44 (1): 73–78. doi:10.1016/S0039-6257(99)00039-9. ISSN 0039-6257. PMID 10466590.

- Magdalino, Paul (2002). The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521526531.

- Magdalino, Paul (2008). "The empire of the Komnenoi (1118–1204)". The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c. 500–1492. Cambridge University Press. pp. 627–663. ISBN 978-0-521-83231-1.

- Minorsky, Vladimir (1945), "Khāqānī and Andronicus Comnenus", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 11 (3), University of London: 557–558, doi:10.1017/s0041977x0007227x, S2CID 161748303

- Norwich, John Julius (1998). A Short History of Byzantium. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-192859-3.

- Norwich, John Julius (2018). The Kingdom in the Sun, 1130–1194. Faber & Faber. ISBN 9780571346097.

- Savvides, Alexis G. K. (1994). "Notes on 12th-century Byzantine Prosopography (Aaron Isaacius-Stephanus Hagiochristophorites)". Vyzantiaka. 14. Thessaloniki: 341–353.

- Siecienski, A. Edward (2023). Beards, Azymes, and Purgatory: The Other Issues that Divided East and West. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-006506-5.

- Spinei, Victor (2009), The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth century, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-17536-5

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Varzos, Konstantinos (1984). Η Γενεαλογία των Κομνηνών [The Genealogy of the Komnenoi] (PDF) (in Greek). Vol. A. Thessaloniki: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Thessaloniki. OCLC 834784634.

- Varzos, Konstantinos (1984). Η Γενεαλογία των Κομνηνών [The Genealogy of the Komnenoi] (PDF) (in Greek). Vol. B. Thessaloniki: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Thessaloniki. OCLC 834784665.

- Venning, Timothy (2015). A Chronology of the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-80269-8.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Andronikos I Komnenos at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Andronikos I Komnenos at Wikimedia Commons